Scene Questions: Give Your Scenes Shape and Momentum

craft post by Anne-Marie Strohman

I’ve been writing a lot about questions lately--specifically questions readers ask while they’re reading our work, and how to control what questions they ask to focus your work and make it more compelling to readers. This can happen by introducing a strong STORY QUESTION that lasts the length of the novel, and by using a combination of WONDERING QUESTIONS in your first chapter(s) to lead up to your STORY QUESTION (see Part 2 here).

Today I want to talk about how using questions can help in the rest of your novel, by talking about SCENE QUESTIONS.

What is a SCENE QUESTION?

A SCENE QUESTION is a story question on a smaller scale. Introduced at or near the beginning of a scene (or even at the end of the previous scene), the scene question is a yes/no question that will drive the tension in the scene and keep readers turning pages so they can find out the answer.

Will Gracia win the gymnastic meet?

Will Tyrian learn the basics of sword fighting?

Will Gigi win the election for class president?

Will Sage convince her best friend not to date the bad guy?

Let’s Take a Look

Every author uses scene questions, whether they know it or not. It’s a natural and effective technique for creating forward momentum. Take the cliffhanger, for instance. It’s the technique of introducing a scene question and then making readers wait for it to be answered--we want to know what happens.

In KidLit, you can look to any category for examples--young adult, middle grade, picture books (where scene questions are what make for great page turns). Today, I’m going to use an example from a chapter book, so we can look at the scene in its entirety.

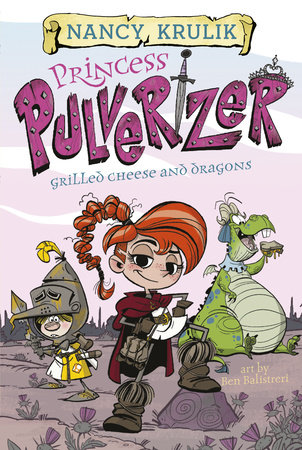

In Princess Pulverizer: Grilled Cheese and Dragons by Nancy Krulik, Princess Serena, AKA Princess Pulverizer, wants to go to Knight School. To prove to her father that she has what it takes to be a knight, she must go on a Quest of Kindness to complete eight selfless good deeds. Chapter 3 begins with her first opportunity for a good deed. See if you can identify the scene question and the answer.

“Here, let me help you carry that heavy basket,” Princess Pulverizer said the next morning as she came upon an old woman carrying a basket filled with potatoes.

The princess grinned widely as she spoke. She was just beginning her quest and hadn’t gotten any farther than a small village on the outskirts of Empiria. Yet already she had found someone who appeared to need her help. What luck!

Princess Pulverizer tried to take the basket from the old woman’s hands. But the woman wouldn’t let go.

“Get your hands off my basket!” she demanded.

“But you have to let me help you,” Princess Pulverizer insisted. She pulled harder at the basket.

“Let go of my potatoes!” The old woman gripped the basket tightly.

“I need to do a good deed,” Princess Pulverizer explained. She gave another tug and . . . .

Rrrippp. The basket broke open.

Thump.

Bump.

Flump.

The potatoes fell into the mud.

“Look what you’ve done!” the old woman scolded her. “My basket is torn. How am I supposed to get my potatoes home now?”

“I’ll help you carry them,” Princess Pulverizer suggested. “That would be a good deed, right?”

“I think you’ve done enough,” the old woman said. “Go on your way.”

“Can I at least take one of these potatoes as a token--just to show my father that I tried to do a good deed?” Princess Pulverizer asked.

“First you break my basket and now you want to steal one of my potatoes?” The woman gasped.

“I don’t want to steal it, I just--” Princess Pulverizer began to explain.

But the old woman didn’t let her finish. “HELP!” she shouted. “THIEF!” (30-34)

With the context of the STORY QUESTION--Will Princess Pulverizer complete her Quest of Kindness and earn a place at Knight School?--the first sentence gives us the scene question: Will Princess Pulverizer perform her first good deed? or more specifically, Will Princess Pulverizer help the woman with her potatoes?

Notice at the beginning, the author leads with the scene question, then orients the reader in time, place, and status of the quest. This strategy hooks readers in right away and also makes sure they know exactly where they are in the story. As the scene goes on, things are not looking good for Princess Pulverizer. She rips the bag. The potatoes fall.

The answer to the question is sealed when the woman says “You’ve done enough. Go on your way”: NO, Princess Pulverizer does not complete a good deed. In response, she pushes just a little more, AND THEN she is accused of being a thief--the story gets a little more complicated, and Princess Pulverizer must respond to what happens after she fails.

What a Scene Question Does

A scene question introduces tension. Readers want to know the answer and will turn pages to find out. Beginning and ending a scene with a question and its answer gives a scene shape.

Scene questions also provide a direction for readers. Readers know why they are reading what they’re reading. The other parts of the story are put in the context of actions that matter.

Scene questions provide momentum in moving from one scene to the next. They can provide causal relationships between scenes.

Do you have to have scene questions? No. But it can make your job as a writer easier. You will need times where a character reflects and decides what to do next. Those moments can happen within a scene, or at the end of a scene. Sometimes these moments will function outside of the question/answer structure, but should be directly relevant to it.

Effective (and Ineffective) Answers to Scene Questions

You have six main ways to answer that yes/no scene question:

YES.

NO.

YES, BUT.

YES, AND

NO, AND.

NO, BUT.

YES. The first option effectively ends the story. Will Gracia win the gymnastics meet? YES! Triumph. Win. Story over. If this question is near the end of the novel and in the climatic scene, YES can be a perfect answer. All that’s left after the final YES is to show the resolution of the story--how that climactic scene changes the lives of the characters.

NO. The second option leaves the reader at sea. Will Tyrian learn the basics of sword fighting? NO. Defeat. Loss. Maybe humiliation. But what now? What happens next? If he has failed so completely that he’s given up entirely, the story also effectively ends, or readers have to sit through pages and pages of Tyrian mourning his loss.

The next four answers have more potential to drive the momentum of the story.

YES, BUT is a fantastic answer to a scene question. Will Gigi win the election for class president? YES, BUT her arch nemesis wins vice president and his minions win secretary and treasurer. The character succeeds, but additional obstacles are placed in her way. The story must continue.

YES, AND is weaker and should be used with caution. It can lead to unrelated positive elements being added to the story, and they may not connect clearly to the story question. Typically, stories need more obstacles and failures, not more successes. Let’s visit our friend Gigi again: Will Gigi win the election? YES, AND she also becomes a National Merit Scholar. We’re proud of Gigi, but we might ask “So what?” What does being a Merit Scholar have to do with the election, Gigi’s emotional growth, and the overall story? A YES, AND doesn’t launch us clearly into the next scene. However, you may be building one success after another on purpose to make the fall that much worse.

NO, AND can also be a strong scene ender that helps the story continue. Will Sage convince her best friend not to date Bad Guy? NO, AND her best friend pressures Sage to go on a double date with her and Bad Guy. Not only did Sage fail, she’s got additional pressures added to the mix. We saw this answer in the Princess Pulverizer scene. NO, she does not do a good deed, AND she is accused of being a thief. She fails and has additional complications.

NO, BUT can have some power too, but it will take the story in a new direction. Let’s take our friend Tyrian the aspiring sword-fighter again. Will Tyrian learn the basics of sword fighting? NO, BUT he manages to impress the Queen with his fancy footwork, and she invites him to take dancing lessons. Here Tyrian’s failure leads him to success in another area--the story turns from sword fighting to dancing. Depending on the overall STORY QUESTION, this may or may not work in the story as a whole. It can be the catalyst for an unexpected twist, as we’ll see below.

How Scene Questions Relate to the Story as a Whole

A story can be seen as a series of SCENE QUESTIONS that build from one to the next. Writers can help shape the readers’ questions, then answer those questions. But if these scene questions have little to do with the larger story question, they may be for naught.

In the Tyrian example, if his STORY QUESTION is Will Tyrian save his younger brother from a slime-spitting beast? The NO, BUT shift from sword fighting to dancing could be a wonderful twist--he’s going to somehow use his dancing skills to best the beast--or it could be a dead-end--he no longer has any chance to save his brother and he has to give up.

As you’re shaping your scene questions and answering them, keep in mind your overarching story question. Most scene questions will be on a path that leads to the answer to the main story question, even if they seem slant at first.

Now it’s your turn

Analyze your scenes for scene questions:

Do you introduce a question into the readers’ minds for the scene?

When does it show up? End of the last scene? Beginning of the current scene? Partway through the current scene?

How do you answer the scene question?

When does the answer show up? At the end of the scene? In the middle of the scene?

Is it a strong answer that keeps the moment of the story moving into the next scene?

If your scenes are lacking tension, try introducing a scene question at or near the beginning of the scene and answering it at or near the end of the scene.

If your scenes don’t seem to flow from one to the next, try setting up the scene question for the current scene at the end of the scene before it. (NO, AND and YES, BUT answers often do this automatically.)

Make a list or spreadsheet of your scene questions and answers. Read them in order. This strategy can help you identify if you have scenes that are out of order, or if the scenes can be in a more logical order.